This is the third part of the second of twenty-five weekly articles in The Tennessee Star’s Constitution Series. Students in grades 8 through 12 can sign up here to participate in The Tennessee Star’s Constitution Bee, which will be held on September 23.

The Separation of Powers between three equal branches of the national government–legislative, executive, and judicial– along with Federalism are the two foundational concepts of the Constitution of the United States that protect the freedoms and liberties guaranteed to individual citizens.

Both foundational concepts are the practical implementation of the Founding Fathers’ belief in the need for checks and balances to prevent the rise of uncontrolled abuses of power within one branch of government.

“It is safe to say that a respect for the principle of separation of powers is deeply ingrained in every American,” the National Archives website says:

The nation subscribes to the original premise of the framers of the Constitution that the way to safeguard against tyranny is to separate the powers of government among three branches so that each branch checks the other two. Even when this system thwarts the public will and paralyzes the processes of government, Americans have rallied to its defense.

One Founding Father, more than any other, was the driving force behind the inclusion of The Separation of Powers as a foundational concept in the Constitution: James Madison, an intellectual giant who was only 26 years old when he arrived in Philadelphia in May 1787 to sit as one of fifty-five delegates to the Constitutional Convention. Young Madison, a graduate of Princeton University, came prepared. He had spent months reviewing other forms of government throughout history and arrived with voluminous notes and a detailed outline of how he thought the Constitution should be written. To a large extent, the final document followed much of that outline.

“Madison argues, it is not sufficient to establish separation of powers on parchment only. Because men are not angels—because they are so often actuated by private interest and ambition—these very motives themselves must be employed to keep the departments of government within their limited, constitutional boundaries,” the Heritage Foundation writes of the bookish young man who arrived in Philadelphia wise beyond his years.

“Ambition must be made to counteract ambition. The interest of the man must be connected with the constitutional rights of the place,” the author of Federalist No. 51 wrote in early 1788 as the states were selecting delegates to attend the state conventions and debate the ratification of the Constitution. Madison probably authored that essay, though it may have been Alexander Hamilton.

“Madison thus proposed a system of checks and balances that would incorporate the less than sterling side of human nature into the very workings of government,” the Heritage Foundation notes:

To accomplish this, the powers of the three branches of government are partially blended, enabling each branch to guard against usurpations of power by the others and safeguard its own constitutional province. Examples of constitutional checks and balances include the executive veto of legislative bills, the legislative override of the executive veto, the required Senate confirmation of presidential appointments to the Supreme Court, and judicial review.

In essence, Madison wanted the different branches of government, as well as the two houses of Congress and the national and the state governments, to check each other in the exercise of power, thereby guaranteeing the diffusion of governmental power and the protection of the people’s rights and liberties.

“The accumulation of all powers, legislative, executive, and judiciary, in the same hands, whether of one, a few, or many, and whether hereditary, self appointed, or elective, may justly be pronounced the very definition of tyranny,” James Madison wrote in Federalist Paper #47, first published in The New York Packet on February 1, 1788.

“The preservation of liberty requires that the three great departments of power should be separate and distinct,” he noted in that essay.

“Where the WHOLE power of one department is exercised by the same hands which possess the WHOLE power of another department, the fundamental principles of a free constitution are subverted,” he added.

The end result that emerged on parchment of this scheme of “checks and balances” known as The Separation of Powers designated specific powers to each of the three branches of the national government.

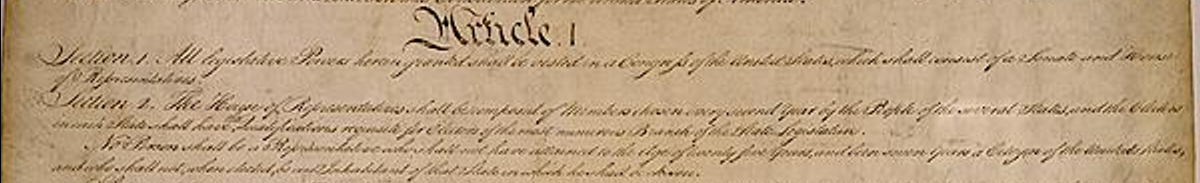

Article I, Section 8 of the Constitution enumerates 19 specific powers granted to the legislative branch of the national government:

(1) The Congress shall have Power To lay and collect Taxes, Duties, Imposts and Excises,

(2) to pay the Debts and provide for the common Defence and general Welfare of the United States; but all Duties, Imposts and Excises shall be uniform throughout the United States;

(3) To borrow Money on the credit of the United States;

(4) To regulate Commerce with foreign Nations, and among the several States, and with the Indian Tribes;

(5) To establish an uniform Rule of Naturalization, and uniform Laws on the subject of Bankruptcies throughout the United States;

(6) To coin Money, regulate the Value thereof, and of foreign Coin, and fix the Standard of Weights and Measures;

(7) To provide for the Punishment of counterfeiting the Securities and current Coin of the United States;

(8) To establish Post Offices and post Roads;

(9) To promote the Progress of Science and useful Arts, by securing for limited Times to Authors and Inventors the exclusive Right to their respective Writings and Discoveries;

(10) To constitute Tribunals inferior to the supreme Court;

(11) To define and punish Piracies and Felonies committed on the high Seas, and Offences against the Law of Nations;

(12) To declare War, grant Letters of Marque and Reprisal, and make Rules concerning Captures on Land and Water;

(13) To raise and support Armies, but no Appropriation of Money to that Use shall be for a longer Term than two Years;

(14) To provide and maintain a Navy;

(15) To make Rules for the Government and Regulation of the land and naval Forces;

(16) To provide for calling forth the Militia to execute the Laws of the Union, suppress Insurrections and repel Invasions;

(17) To provide for organizing, arming, and disciplining, the Militia, and for governing such Part of them as may be employed in the Service of the United States, reserving to the States respectively, the Appointment of the Officers, and the Authority of training the Militia according to the discipline prescribed by Congress;

(18) To exercise exclusive Legislation in all Cases whatsoever, over such District (not exceeding ten Miles square) as may, by Cession of particular States, and the Acceptance of Congress, become the Seat of the Government of the United States, and to exercise like Authority over all Places purchased by the Consent of the Legislature of the State in which the Same shall be, for the Erection of Forts, Magazines, Arsenals, dock-Yards, and other needful Buildings;—And

(19) To make all Laws which shall be necessary and proper for carrying into Execution the foregoing Powers, and all other Powers vested by this Constitution in the Government of the United States, or in any Department or Officer thereof.

Article II, Sections 2 and 3 of the Constitution enumerates 13 specific powers granted to the executive branch of the national government:

Section. 2.

(1) The President shall be Commander in Chief of the Army and Navy of the United States, and of the Militia of the several States,

(2) he may require the Opinion, in writing, of the principal Officer in each of the executive Departments, upon any Subject relating to the Duties of their respective Offices,

(3) and he shall have Power to grant Reprieves and Pardons for Offences against the United States, except in Cases of Impeachment.

(4) He shall have Power, by and with the Advice and Consent of the Senate, to make Treaties, provided two thirds of the Senators present concur;

(5) and he shall nominate, and by and with the Advice and Consent of the Senate, shall appoint Ambassadors, other public Ministers and Consuls, Judges of the supreme Court, and all other Officers of the United States, whose Appointments are not herein otherwise provided for, and which shall be established by Law:

(6) the Congress may by Law vest the Appointment of such inferior Officers, as they think proper, in the President alone, in the Courts of Law, or in the Heads of Departments.

(7) The President shall have Power to fill up all Vacancies that may happen during the Recess of the Senate, by granting Commissions which shall expire at the End of their next Session.

Section. 3.

(8) He shall from time to time give to the Congress Information of the State of the Union, and recommend to their Consideration such Measures as he shall judge necessary and expedient;

(9) he may, on extraordinary Occasions, convene both Houses, or either of them,

(10) and in Case of Disagreement between them, with Respect to the Time of Adjournment, he may adjourn them to such Time as he shall think proper;

(11) he shall receive Ambassadors and other public Ministers;

(12) he shall take Care that the Laws be faithfully executed, and

(13) shall Commission all the Officers of the United States.

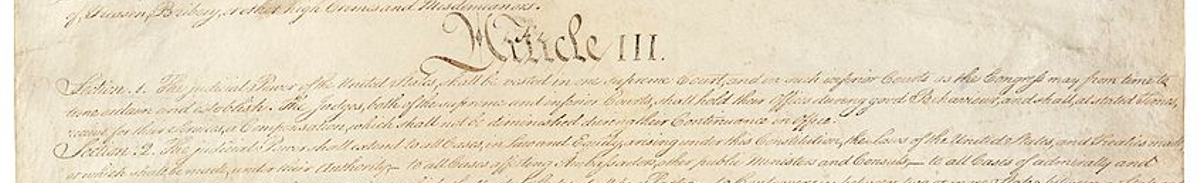

Article III, Section 2 of the Constitution enumerates one specific power granted to the judicial branch of the national government:

(1) The judicial Power shall extend to all Cases, in Law and Equity, arising under this Constitution, the Laws of the United States, and Treaties made, or which shall be made, under their Authority;

It also defines 8 specific types of cases to which the judicial power of the judicial branch of the national government shall apply:

(1) to all Cases affecting Ambassadors, other public Ministers and Consuls;

(2) to all Cases of admiralty and maritime Jurisdiction;

(3) to Controversies to which the United States shall be a Party;

(4) to Controversies between two or more States;

(5) between a State and Citizens of another State,

(6) between Citizens of different States,

(7) between Citizens of the same State claiming Lands under Grants of different States,

(8) and between a State, or the Citizens thereof, and foreign States, Citizens or Subjects.

Over the next 228 years, as Madison predicted “Because men are not angels—because they are so often actuated by private interest and ambition,” the checks and balances designated in the parchment of the Constitution has been transformed by the practices of non-angelic men and women to create a system of government that deviates substantially from the one envisioned by the Founding Fathers in two very specific ways:

First, the national government has continually usurped the power of the state governments, as envisioned in the foundational concept of Federalism.

Second, The Separation of Powers within the national government has evolved dramatically, as both the executive branch and the judicial branch have assumed greater and greater powers, while the legislative branch has abrogated–informally in many instances–some of its most important constitutional powers.

“Abrograte” is a strong word, not often used.

Dictionary.com defines its meaning as “to abolish by formal or official means; annul by an authoritative act; repeal,” or “to put aside; put an end to.”

It is in the nineteenth enumerated power in which the legislative branch has failed so dramatically:

To make all Laws which shall be necessary and proper for carrying into Execution the foregoing Powers, and all other Powers vested by this Constitution in the Government of the United States, or in any Department or Officer thereof.

The legislative branch has given away huge powers to the executive branch in the form of specific regulatory rule making based upon laws passed in Congress. This sacrifice of authority has given rise, over the past century, to the runaway regulatory bureaucratic state.

The details of how this came about will be the topic of several articles in the remaining 25 articles in The Tennessee Star’s Constitution Series.

[…] Download Image More @ tennesseestar.com […]

[…] of those states, to form a government guided by the foundational principles of Federalism and the Separation of Powers as defined in the Constitution and the Bill of […]

[…] The Separation of Powers […]